Touch forms bonds and boosts immune systems

/Miss hugs? Touch forms bonds and boosts immune systems. Here’s how to cope without it during coronavirus

Don’t shake hands, don’t high-five, and definitely don’t hug.

We’ve been bombarded with these messages during the pandemic as a way to slow the spread of COVID-19, meaning we may not have hugged our friends and family in months.

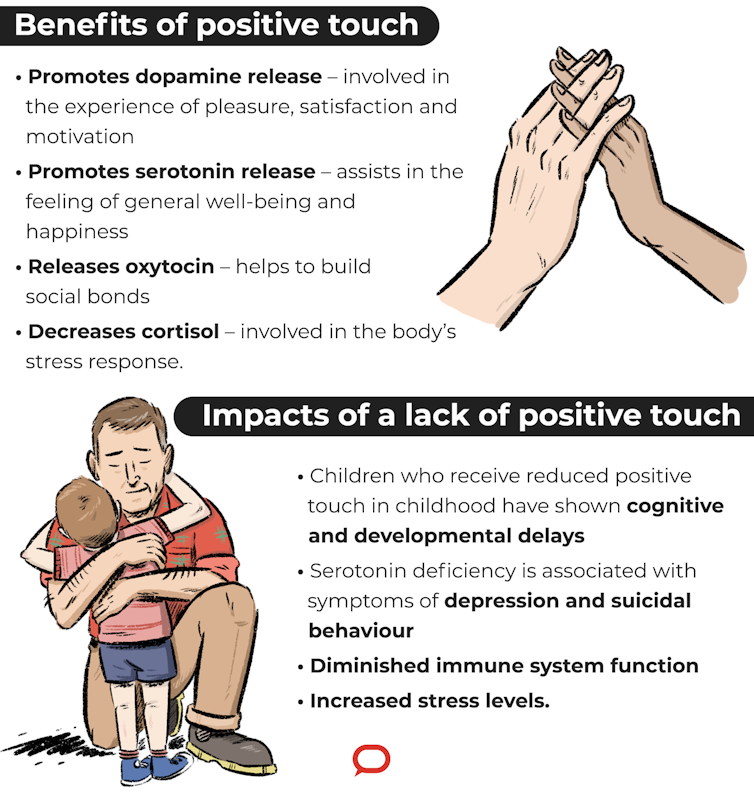

This might be really hard for a lot of us, particularly if we live alone. This is because positive physical touch can make us feel good. It boosts levels of hormones and neurotransmitters that promote mental well-being, is involved in bonding, and can help reduce stress.

So how can we cope with a lack of touch?

Touch helps us bond

In humans, the hormone oxytocin is released during hugging, touching, and orgasm. Oxytocin also acts as a neuropeptide, which are small molecules used in brain communication.

It is involved in social recognition and bonding, such as between parents and children. It may also be involved in generosity and the formation of trust between people.

Touch also helps reduce anxiety. When premature babies are held by their mothers, both infants and mothers show a decrease in cortisol, a hormone involved in the stress response.

Touch promotes mental well-being

In adults with advanced cancer, massages or simple touch can reduce pain and improve mood. Massage therapy has been shown to increase levels of dopamine, a neurotransmitter (one of the body’s chemical messengers) involved in satisfaction, motivation, and pleasure. Dopamine is even released when we anticipate pleasurable activities such as eating and sex.

Read more: We need to flatten the 'other' coronavirus curve, our looming mental health crisis

Disruptions to normal dopamine levels are linked to a range of mental illnesses, including schizophrenia, depression and addiction.

Serotonin is another neurotransmitter that promotes feelings of well-being and happiness. Positive touch boosts the release of serotonin, which corresponds with reductions in cortisol.

Serotonin is also important for immune system function, and touch has been found to improve our immune system response.

Symptoms of depression and suicidal behaviour are associated with disruptions in normal serotonin levels.

But what about a lack of touch?

Due to social distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, we should be vigilant about the possible effects of a lack of physical touch, on mental health.

It is not ethical to experimentally deprive people of touch. Several studies have explored the impacts of naturally occurring reduced physical touch.

For example, living in institutional care and receiving reduced positive touch from caregivers is associated with cognitive and developmental delays in children. These delays can persist for many years after adoption.

Read more: Childhood deprivation affects brain size and behaviour

Less physical touch has also been linked with a higher likelihood of aggressive behaviour. One study observed preschool children in playgrounds with their parents and peers, in both the US and France, and found that parents from the US touched their children less than French parents. It also found the children from the US displayed more aggressive behaviour towards their parents and peers, compared to preschoolers in France.

Another study observed adolescents from the US and France interacting with their peers. The American kids showed more aggressive verbal and physical behaviour than French adolescents, who engaged in more physical touch, although there may also be other factors that contribute to different levels of aggression in young people from different cultures.

Maintain touch where we can

We can maintain touch with the people we live with even if we are not getting our usual level of physical contact elsewhere. Making time for a hug with family members can even help with promoting positive mood during conflict. Hugging is associated with smaller decreases in positive emotions and can lessen the impact of negative emotions in times of conflict.

In children, positive touch is correlated with more self-control, happiness, and pro-social skills, which are behaviours intended to benefit others. People who received more affection in childhood behave more pro-socially in adulthood and also have more secure attachments, meaning they display more positive views of themselves, others, and relationships.

Pets can help

Petting animals can increase levels of oxytocin and decrease cortisol, so you can still get your fill of touch by interacting with your pets. Pets can reduce stress, anxiety, depression and improve overall health.

In paediatric hospital settings, pet therapy results in improvements in mood. In adults, companion animals can decrease mental distress in people experiencing social exclusion.

Read more: Are people with pets less likely to die if they catch the coronavirus?

What if I live alone?

If you live alone, and you don’t have any pets, don’t despair. There are many ways to promote mental health and well-being even in the absence of a good hug.

The American College of Lifestyle Medicine highlights six areas for us to invest in to promote or improve our mental health: sleep, nutrition, social connectedness, exercise, stress management, and avoiding risky substance use. Stress management techniques that use breathing or relaxation may be a way to nurture your body when touch and hugs aren’t available.

Staying in touch with friends and loved ones can increase oxytocin and reduce stress by providing the social support we all need during physical distancing.

This article is supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.![]()

Michaela Pascoe, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Mental Health, Victoria University; Alexandra Parker, Professor of Physical Activity and Mental Health, Victoria University; Glen Hosking, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Victoria University, and Sarah Dash, Postdoctoral research fellow, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.