Is hip dysplasia in my newborn something to worry about?

/Is hip dysplasia in my newborn something to worry about?

This is part of our series on kids’ health. Read the other articles in our series here.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip, sometimes termed congenital dysplasia or dislocation of the hip, is a chronic condition present from early childhood which can cause permanent disability if not identified and treated early.

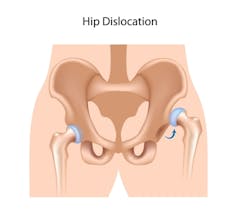

Hip dysplasia affects up to 10 people in every 1,000, and is characterised by underdevelopment of the hip bones (dysplasia). This may be associated with laxity (looseness) or even dislocation of the hip joints. It may affect one or both hips.

The hips are ball-and-socket joints. These develop while a baby is still in the uterus, as well as in early childhood. In a newborn infant, most of the hip joint is cartilage, which is soft and may contribute to the laxity of the joint. During the baby’s first year, the cartilage is replaced by bone.

In normal hip development, the ball component grows faster than the socket. The development of the joint is dependent on the ball component remaining within the socket. Various factors may affect the development of the joint, along with the ligaments which support the joint and hold the two bony components together.

In hip dysplasia, the socket component (acetabulum) is underdeveloped, so the ball component is not well fixed in the socket. This means that the hip is more prone to dislocation, where the ball slides out of the socket. This can cause serious problems for the blood supply to the hip, and also affect walking.

Causes

Anything that reduces or prevents movement of the hip joint increases the risk of hip dysplasia. Large babies, reduced amniotic fluid or a first pregnancy (with a less “stretchy” uterus) reduce the space a baby has to move around when still in the uterus.

Being breech (bottom instead of head first) at delivery and tight swaddling during early childhood also increase the risk of hip dysplasia.

Babies who have someone in their immediate family with hip dysplasia are more likely to be affected. Females are four times more likely to be affected than males. This is probably related to hormones the mother produces, which cause ligaments to be more relaxed around the time of birth. Girls may be more sensitive to these hormones than boys.

Diagnosis

There are usually no symptoms of hip dysplasia at birth, as babies are not able to walk or crawl. Because of the risks of disability if not detected, all babies undergo screening, usually physical examination by a trained midwife or doctor at birth and again at the routine six-week check.

Ongoing examinations take place over the first 12 months. At these examinations, clinicians feel for laxity of the hip joints. This may be felt as a looseness of the joint, or hips which do not stay in the joint (dislocate) when moved.

Other signs may include an asymmetry of the buttock creases or leg lengths (due to one hip not being fully located in the joint). Not all cases of laxity mean that the child has dysplasia, and not every case of dysplasia will be detected by this clinical examination as the condition develops with time.

Those with risk factors such as being born breech often have enhanced screening, such as an ultrasound.

An X-ray may be used in older children or adults to demonstrate the underdeveloped socket of the hip. An X-ray is less useful in younger infants as the hips still contain a large proportion of cartilage, which is not so well seen on X-ray.

If dysplasia is not detected through infant screening, older children or adults may present with difficulty walking, a limp, arthritis, or pain.

Treatment

Most babies with slightly lax hips at birth usually resolve by six weeks without any treatment. Those with lax hips that don’t resolve should begin treatment by six to eight weeks. If a baby has a dislocated hip, treatment should start immediately.

A harness is usually used to treat dysplasia in infants. This holds the hips bent forward and held out, to maximise the contact between the ball and socket.

The harness is removable for washing and is otherwise worn continuously for three to seven months. Previously, wearing two or three nappies instead of one was used as a treatment. This has not been shown to be effective, and may delay treatment with an appropriate harness.

The main (but rare) possible side effect to wearing a harness is avascular necrosis (the death of bone tissue). This is thought to be caused by the ball component of the hip being pressed hard against the socket. The result is squashing of the blood vessels supplying the bone, which might reduce the blood supply there. This can result in arthritis and damage to the bone. It is more likely if treatment starts late.

Surgery is sometimes undertaken, although most cases (up to 95%) resolve with early application of a harness. Surgery is only used if harness treatment is unsuccessful, or if a patient presents later than infancy. Surgery for hip dysplasia has a higher risk of avascular necrosis than harnesses.

Long term effects

Developmental dysplasia of the hip can cause significant long term problems if it is not identified and treated early. These include early (from before age 30) arthritis, back pain, need for multiple surgeries, and a shorter leg on one side.

With early treatment, the rate of later hip problems requiring further treatment is very low (around 4%).

To minimise risk of later disability, parents whose newborn has some of the risk factors should discuss this with their doctor to ensure adequate examination and screening.

Further reading:

Do kids grow out of childhood asthma?

A snapshot of children’s health in Australia

Nightmares and night terrors in kids: when do they stop being normal?

Bed-wetting in older children and young adults is common and treatable

Migraines in childhood and adolescence: more than just a headache

‘Slapped cheek’ syndrome: a common rash in kids, more sinister in pregnant women

![]() Teenage pain often dismissed as ‘growing pains’, but it can impact their lives

Teenage pain often dismissed as ‘growing pains’, but it can impact their lives

Kirsten Thompson, Senior clinical lecturer, University of Western Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.